Have you been told you have a “hormone imbalance” or “oestrogen dominance”?

Do you experience issues with anxiety, brain fog, irregular periods and headaches?

You may be experiencing histamine overload or intolerance. But what is histamine, and what does it have to do with periods? In this blog post we look at all things histamine, oestrogen, and menstrual health, and ways to help reduce the impact of this molecule on your cycle.

What is Histamine?

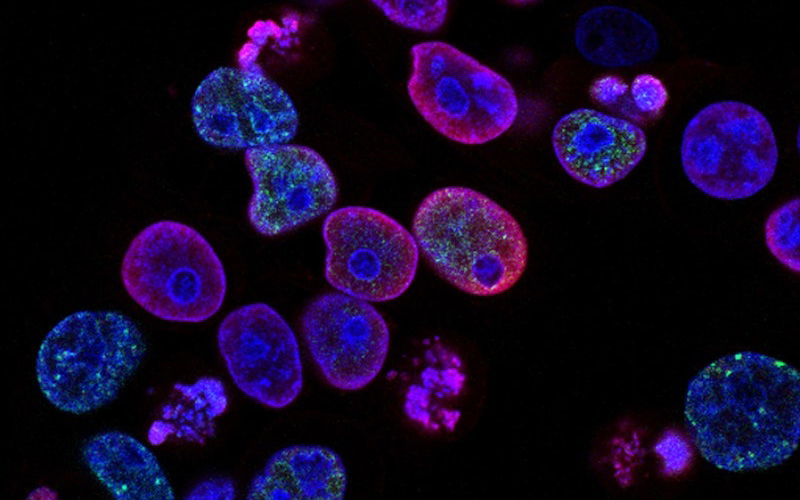

Histamine is an important molecule in the body that is involved in immune, allergy and inflammation pathways. Histamine is a type of biologically active amine (also known as a “biogenic amine”), a group of many different amino acids that cause changes in the body. Histamine is stored and produced in many different cells within the body, however one of the main cells associated with histamine and its production are mast cells, an immune system cell that makes up part of our innate immune system. Mast cells produce and store histamine inside their cell walls, and then release it in response to certain stimuli, such as exposure to allergenic substances (e.g. foods, pollens, etc.).

You may be familiar with the term “anti-histamines” and assume that histamine is therefore something we need to eliminate completely, however histamine is an essential part of our body’s functioning and is responsible for many diverse effects in the body. One of the most recognisable effects of histamine is in response to allergens – it is histamine that is responsible for the tell-tale runny nose, watering eyes and itchy skin we associate with allergies. It is an important part of our innate immune system, is involved in neurotransmitter release, and may even play a role in ovulation (as well as implantation, uterine contractions, and even lactation).

Too much histamine, however, can cause health issues. Recurring hives and chronic allergic-type symptoms are a sign that your histamine levels are too high (histamine overload) or are exceeding the amount your body is able to cope with (histamine intolerance). Excess histamine is also associated with conditions such as interstitial cystitis (“painful bladder syndrome”), pre-eclampsia and preterm delivery, and menstrual conditions such as PMS and endometriosis.

Our bodies are able to process and neutralise histamine via enzymes, particularly diamine oxidase (DAO). Whilst we all possess enzymes to break down histamine, there is a limit to how much histamine these enzymes can process, a limit known as “histamine tolerance”. If our bodies exceed this limit, we end up in “histamine intolerance”, leading to excess histamine circulating throughout the body and causing symptoms. Deficiencies in the micronutrients required for producing DAO (particularly B vitamins such as B6 and vitamin C), as well as gastrointestinal conditions such as Crohn’s disease and even dysbiosis/SIBO, can negatively impact on our DAO levels and leave us at greater risk of histamine overload.

Signs that you might be experiencing histamine issues (e.g. histamine overload or histamine intolerance):

- Headaches or migraines

- Hives, itching skin

- Irregular periods, PMS symptoms (breast pain, cramps)

- Fatigue and brain fog

- Nausea and vomiting

- Nasal congestion, sinus issues

- Anxiety

- Mood changes

- Asthma

How Can Histamine Affect Oestrogen?

So what exactly does histamine have to do with hormones? It turns out, a lot. Histamine and oestrogen are linked – the number of mast cells, and the amount of histamine they produce, fluctuates throughout the menstrual cycle, rising as oestrogen levels rise and falling as oestrogen levels fall. Oestrogen increases histamine levels by triggering mast cells to release their stored histamine and also down-regulates DAO, the enzyme responsible for clearing excess histamine from the body. Progesterone, on the other hand, reduces the release of histamine and increases DAO activity, providing balance. This effect of hormones on mast cells and histamine levels has been demonstrated with skin prick allergy tests – changes to hormone levels throughout the menstrual cycle can affect your test results! A 1995 study found that skin prick testing revealed higher histamine levels in women during days 12-16 of their cycle, during ovulation and when oestrogen is at its highest. Because of this link between oestrogen and histamine, women tend to have higher levels of histamine than men and are therefore predisposed to histamine intolerance. This link between histamine and female hormones also helps to explain why symptoms for some women are worse at certain points during the menstrual cycle, such as during ovulation.

When oestrogen levels become too high compared to progesterone, (e.g. oestrogen dominance), a feedback loop occurs between oestrogen and histamine; oestrogen stimulates mast cells to release more histamine, and histamine stimulates the ovaries to produce more oestrogen, further worsening the oestrogen dominance. It is this feedback loop that leads to histamine’s impact on female hormonal issues, and why focusing on reducing excess oestrogen as well as reducing histamine can help to quell symptoms.

Elevated histamine levels have been shown in women with endometriosis and even correspond with higher levels of pain experienced by these women. Histamine may also contribute to certain symptoms of PMS, such as headaches, breast pain, and anxiety, due to the increase of histamine when oestrogen levels rise just before menstruation. Histamine can also wreak havoc on your health during perimenopause. Whilst most of us understand that our oestrogen levels drop after menopause, during the perimenopausal period (the 1-10 years leading up to menopause), our oestrogen levels are far more variable. In fact, oestrogen levels can actually be up to 3 times higher than normal during this time! Combined with changes to thyroid hormone production that often occur at this time (and can also impact histamine levels), it’s no wonder many women will develop symptoms of histamine intolerance during this period of their lives.

Reducing the Impact of Histamine on Your Menstrual Health

The good news is there are many strategies for reducing the impact of histamine on your menstrual health. Some of the key ways to help reduce your histamine load include:

- Reduce your intake of high histamine foods

- Reduce your intake of foods that increase production of histamine in the body

- Reduce excess oestrogen in the body

Foods that are high in histamine:

- Alcoholic drinks, including wine (particularly red wine), beer and whiskey

- Highly processed or smoked meats such as salami, bacon, hot dogs, and pepperoni

- Fermented foods, such as kombucha, kefir, kim chi, sauerkraut and even vinegar

- Fermented and/or aged dairy products, including yoghurt and aged cheeses like cheddar, parmesan and swiss cheese

- Dried fruits

- Processed and pre-packaged foods, including condiments such as tomato sauce

- Leftovers, particularly once 24 hours or more old

- Coffee

- Fish and seafood

- Beef

- Strawberries, pineapple, citrus fruits

- Avocado, spinach, eggplant

Foods that trigger histamine release:

While these foods themselves do not contain high amounts of histamine, they can trigger the release of histamine in the body when we eat them, so are best avoided if histamine is triggering your menstrual health issues.

- Bananas, papaya, citrus fruits

- Tomatoes, beans

- Wheat germ

- Chocolate

- Walnuts, cashews, peanuts

Foods that block DAO production:

Remember the enzyme that helps to clear histamine? These foods can stop our body from producing sufficient amounts of DAO and should be avoided.

- Tea, including black, green and mate

- Alcohol

- Energy drinks

Foods that Help to Reduce Histamine

- Vegetables: broccoli, rocket, asparagus, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, carrots, cauliflower, fennel, garlic, kale, onions

- Fruits: apples, blueberries, blackberries, cherries, mangoes

- Dairy-free substitutes such as coconut milk and almond milk

- Gluten-free grains such as rice and quinoa

- Eggs

Supplements to Reduce Histamine

- Quercetin: Quercetin is an important micronutrient when it comes to immune health and can reduce histamine by preventing mast cells from releasing stored histamine. Quercetin can be found in a wide range of low-histamine foods, including apples, berries (except strawberries), onions and green leafy vegetables.

- Vitamin C: Vitamin C is also a powerhouse micronutrient for preventing mast cells from releasing too much histamine. Vitamin C is also an important nutrient for the production of DAO, thus helping to boost the body’s ability to break down histamine. Boost your intake of vitamin C with low-histamine foods such as berries (except strawberries), broccoli, capsicum, and rockmelon.

- Vitamin B6: Vitamin B6 is another nutrient important for DAO production. Increase your intake of vitamin B6 by including freshly cooked meats such as kangaroo, salmon and chicken in your diet.

Other Tips for Reducing Histamine Load

- Purchase your fruits, vegetables and meats as fresh as possible

- Eat foods immediately after cooking

- If you do need to store leftovers, freeze them rather than refrigerating, as this will slow down the production of histamine

- Eat plenty of fibre, which helps to bind and expel excess oestrogen to help naturally balance oestrogen levels

- Avoid inflammatory foods such as gluten, fried foods, and highly processed sugary foods – histamine is released as part of the inflammatory response

- Increase your intake of Brassica vegetables such as broccoli, kale, cauliflower, and Brussels sprouts, which support liver detoxification of excess oestrogen

References

Carr, A. C., & Maggini, S. (2017). Vitamin C and immune function. Nutrients, 9(11).

Ede, G. (2017). Histamine intolerance: Why freshness matters. Journal of Evolution and Health, 2(1).

Fogel, W. A. (1986). Diamine oxidase (DAO) and female sex hormones. Agents Actions, 18(1–2), 44–45.

Jing, H., Wang, Z., & Chen, Y. (2012). Effect of oestradiol on mast cell number and histamine level in the mammary glands of rat. Anatomia Histologia Embryologia, 41(3), 170–176.

Kalogeromitros, D., Katsarou, A., Armenaka, M., Rigopoulos, D., Zapanti, M., & Stratigos, I. (1995). Influence of the menstrual cycle on skin-prick test reactions to histamine, morphine and allergen. Clincial and Experimental Allergy, 25(5), 461–466.

Krishna, A., Beesley, K., & Terranova, P. F. (1989). Histamine, mast cells and ovarian function. Journal of Endocrinology, 120(3), 363–371.

Orazov, M. R., Radzinsky, V. Y., Khamoshina, M. B., Nosenko, E. N., Tokaeva, E. S., Barsegyan, L. K., & Zakirova, Y. R. (2017). Histamine metabolism disorder in pathogenesis of chronic pelvic pain in patients with external genital endometriosis. Patologicheskiaia Fiziologiia i Eksperimental’naia Terapiia, 61(2), 56–60.

Sessa, A., Desiderio, M. A., & Perin, A. (1990). Estrogenic regulation of diamine oxidase activity in rat uterus. Agents Actions, 29(3–4), 162–166.

Shaik, Y., Caraffa, A., Ronconi, G., Lessiani, G., & Conti, P. (2018). Impact of polyphenols on mast cells with special emphasis on the effect of quercetin and luteolin. Central European Journal of Immunology, 43(4), 476–481.

Shan, H., Zhang, E.-W., Zhang, P., Zhang, X.-D., Zhang, N., Du, P., & Yang, Y. (2019). DIfferential expression of histamine receptors in the bladder wall tissues of patients with bladder pain syndrome/ interstitial cystitis—Significance in the responsiveness to antihistamine treatment and disease symptoms. BMC Urology, 19.

Szelag, A., Merwid-Lad, A., & Trocha, M. (2002). Histamine receptors in the female reproductive system. Part I. Role of the mast cells and histamine in female reproductive system. Ginekologia Polska, 73(7), 627–635.

Vasiadi, M., Kempuraj, D., Boucher, W., Kalogeromitros, D., & Theoharides, T. C. (2006). Progesterone inhibits mast cell secretion. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology, 19(4), 787–794.

Zierau, O., Zenclussen, A. C., & Jensen, F. (2012). Role of female sex hormones, estradiol and progesterone, in mast cell behavior. Frontiers in Immunology. https://doi.org/doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2012.00169